“Roaring” Through a Life of Learning

A Vietnamese proverb about a mouse sticking his head in the mouth of a large carnivore may, at first consideration, seem a strange way to view our lives as life-long learners.

“…the mouse does not know life until it has been into the mouth of the cat.”

-Vietnamese proverb

One interpretation of the Vietnamese proverb is to value life because we never know when we’re about to lose it. In other words, enjoy the present. That view, offered up by WikiAnswers.com, is exceptionally shallow and even misleading.

A more useful interpretation of this proverb, when seen in the context of life-long learning, is that of a multi-layered metaphor symbolizing the challenges–and changes–ahead for all of those seeking a life that gains meaning through significant personal growth and intellectual maturation.

When we see the “mouse” as far more than a furry “meal on wheels,” that the proverb is instead, a metaphor for a lengthy, and at times, risky journey toward personal enlightenment and discovery, the daredevil mouse becomes more akin to the “mouse that roared.”

If we “reverse engineer” (work backwards from the product to deduce the process), we find ourselves asking rhetorical questions based on the most important word in our language: Why?

- Why does the “story” begin with the mouse having been to the cat’s mouth?

- Why would the mouse put him/herself in such a suicidal position?

- What were the motivations behind the action? Was it rational or was it irrational?

- How did the mouse escape the cat?

We ask such questions out of curiosity, but also because we need answers to better understand the real value of this proverb–to focus less on the journey and more on the destination.

What is the Truth? What really happened to bring the mouse and the cat together. What miracle led to the mouse’s escape? Presumably, a wiser mouse, one with valuable lessons to impart to his/her fellow mice about cats and how one’s life changes after such an encounter.

Why do we need to see and learn the Truth as a new meaning for the proverb? Why not just be satisfied with the earlier interpretation that the proverb meant to simply enjoy life?

Perhaps, if we see the “mouse” as Everyman, and the “cat” representing life’s developmental journey, then the metaphor suggests that long-term survival will depend on finding out the Truth–“the rest of the story,” as journalist Paul Harvey often explained. An appropriate analogy can be offered here that long-term “thrival” in the journey through the stages of our lives will depend on an unswerving commitment to finding the Truth about ourselves, how we view the meaning of our lives, and what we see as our destiny.

As a metaphor about a significant life experience, albeit an anthropomorphized mouse, the proverb has much to offer those whose future success depends on applying “critical thinking.” If it were an onion, it would have many layers to peel.

Historians and researchers understandably place a great deal of importance on “primary sources.” When we consult the original primary source–a good dictionary in this instance–for the phrase “critical thinking,” we can establish an important etymological foundation for understanding its relevance for all of us.

The word “critical” traces its origins to Greek (kriterion, a means of judging) and krinein, to separate or choose. In fact, the origins begin in Indo-European with the term “skeri” meaning to cut, separate or sift. (The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 1981) These roots provide a better understanding for the evolution of our word, critical.

The term “critical” can and often is used to mean an inclination to judge severely. However, it has many more nuances and meanings that apply to us at this stage in the doctoral journey. For example, the phrase “critical thinking,” should include the following meanings and core values (operationalized into behaviors) that reflect careful and exact judging based on thorough knowledge through detailed investigations–often accompanied by published arguments articulating the reasons and rationale behind the assessment.

The destination of the “critical thinking” journey is Truth–arrival at a level of subject matter awareness and mastery conferring an exceptional level of understanding–that understanding being characterized by:

- agreement with fact;

- accuracy;

- reliability;

- absence of equivocation; and,

- consistency with fact and reality.

“What a man believes upon grossly insufficient evidence is an index into his desires — desires of which he himself is often unconscious. If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence. The origin of myths is explained in this way.”

-Bertrand Russell

Typically, such journeys of critical thinking put established “truths” at risk or in peril. They often bring us to important turning points where decisive changes are needed, thus fulfilling more of the inherent meaning of “critical.”

Intellectual courage is often tested. Certainly, a fundamental honesty and commitment to fact-based decision making and interpretation is a necessity. Otherwise, more of Russell’s myths will be the likely outcome.

“The weakness of a soul,” pointed out author Eric Hoffer, “is proportionate to the number of truths which must be kept from it.” As Gabennesch (2006) in “Critical Thinking: What Is It Good for? (In Fact, What Is It?),” outlines the sharp and dangerous decline of critical thinking in America–to the level of disagreement as to its very definition–he points to what could be seen as a dangerous, collective weakening of the souls in most Americans.

Gabennesch (2006) provides a gripping recitation of examples where critical thinking has either been misapplied or perhaps even deliberately ignored in numerous publications and policy. His lists of examples lead the reader to ask:

If “critical thinking” is the application of rigorous scientific principles where they can be applied, does the evidence suggest that the search and articulation of truth in the social sciences is being subordinated to other priorities and agendas?

Is the lack of objective “truth” in the social sciences as risky and dangerous as it is in the “pure” sciences?

Is it harder (more nuanced?) to find “truth” in the social sciences, so vulnerable to being overwhelmed by the sheer volume of variables inherent in studying humans, their psychology and sociology?

The “implications of the proverb” on a scientific level suggest the difficulties facing professionals in the social sciences when trying to strictly apply “critical thinking,” exacerbated by disagreement as to its very definition. The numerous examples cited by Gabennesch might also lead readers to question whether enough practitioners have the moral courage needed to find the truth. Perhaps their experience paralleled that of Sir Walter Raleigh:

“It (is) dangerous to follow truth too near, lest she should kick out our teeth.”

-Sir Walter Raleigh

On a personal and a professional level, the proverb, the subject and the readings combine to deliver a message that could be summarized into:

As a dedicated student of life you should internalize the concepts and processes of critical thinking since only by doing so can you expect, after significant effort and application, to reach approximate Truth– a worthy, ultimate goal for all of us.

Life is an expedition through uncharted territory with dangers and pitfalls which can most successfully be negotiated by applying the principles of critical thinking.

For many, there will come a time, perhaps more than once, when it seems as if they were the proverbial mouse having its head in the cat’s mouth. Is not critical thinking the key to a successful escape from the “lion’s den”? Once out of the “shadow of the valley of death,” will the endorphins kick in and we find that we will, henceforth fear no evil? Having survived the trials, will we find life especially meaningful?

The “mouse in the cat’s mouth” proverb can also be seen as an implied metaphor–applied to our quests for degrees and certifications–for the universal “theme of initiation” monomyth. As explained by Joseph Campbell (1973), the initiate Hero, departs the normal world, seeks supernatural assistance, faces a road of trials, reaches an intellectual apotheosis having reached the fount of knowledge and imbibed deeply. Finally, the goal is reached–the ultimate boon–the journey from novice to craftsman is complete.

The metaphorical lesson: the advanced learner and seeker who applies critical thinking rigorously and at times unflinchingly in the face of dangers and pitfalls, will earn the ultimate boon, the achievement of the degree, but more importantly, the boon of advanced competence in finding Truth. Further, mastery of a field, or a competency within that field, offers a degree of freedom from “death,” and therefore confers the freedom to live more fully.

Perhaps following the yellow brick road will be worth it after all, said the mice that roared. Perhaps the first interpretation of the proverb has validity here, as well.

Bibliography

Bensley, D. Alan. (Jul/Aug 2006) Why Great Thinkers Sometimes Fail to Think Critically. The Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 30, Issue 4, pg. 47.

Campbell, Joseph (1973) The Hero With A Thousand Faces. New York: Princeton University Press.

Gabennesch, Howard. (Mar/Apr 2006) Critical Thinking: What Is It Good for? (In Fact, What Is It?). The Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 30, Issue 2, pg. 36, 6 pgs.

© Copyright 2019 BelleAire Press

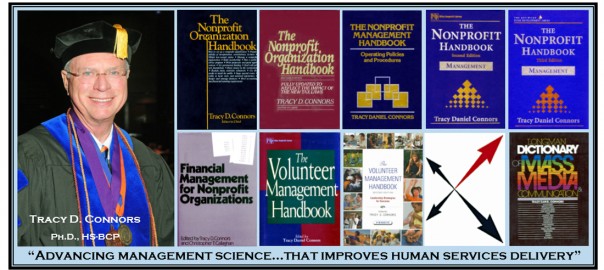

Other works by Dr. Connors…

Baited Trap, the Ambush of Mission 1890

Now Available As E-Pub

Baited Trap, The Ambush of Mission 1890 is the story of helicopter rescue Mission 1890, one of the most heroic—and costly—air rescues of the Korean War. This harrowing Air Force-Navy mission is explained in compelling detail, creating a detailed personal account of what five incredibly brave and determined Air Force and Navy airmen achieved on June 25, 1952 in the infamous “Iron Triangle.”

The Korean War’s Greatest Love Story

Baited Trap is much more than a heroic war story from the “forgotten war.” It is also the Korean War’s greatest love story, following Wayne and Della Lear, Bobby Holloway, Ron Eaton and Dolly Sharp, and Frankie and Archie Connors as they tried to put their lives and families together even as the Korean War was reaching out to engulf them.

Truckbusters From Dogpatch: the Combat Diary of the 18th Fighter-Bomber Wing in the Korean War, 1950-1953

Truckbusters from Dogpatch is the most comprehensive Korean War unit history yet prepared–over 700 pages summarizing squadron histories and first person accounts—and includes over 1,000 never before published photographs and images, highlighted by the 8 ½ x 11-inch format.

Arguably, Truckbusters From Dogpatch is the most authoritative unit history ever prepared on the Korean War. In addition to consulting formerly classified squadron histories filed monthly throughout the conflict, the author was in touch with hundreds of veterans of the 18th—pilots and ground crew—whose personal recollections add vivid detail and emotion to the facts recounted in the official documents.

Recent Log Entries by CAPT Connors…

Carrier Captain’s Night Orders: “Call Me…”

After reading these Night Orders you can better appreciate what training, attention to duty, and vigilance was required by underway watchstanders in those days. What has changed since then that has resulted in the recent tragic collisions between U.S. Navy ships and other vessels?

“We do it all!” (USS Saipan LHA-2 motto)

Saipan CO, CAPT Jack Renard, was not exaggerating when he noted that “without exception, SAIPAN is the most versatile instrument of peace or war on the seas today.” Like its motto pointed out, SAIPAN could do it all.

In Dire Straits of Gibraltar

I had never taken the ship (aircraft carrier F. D. ROOSEVELT) through the Straits before as the OOD. Now I was expected to do so while the rest of the ship—including the Captain—was fast asleep.

U.S. Navy and back to the future Star Power

The reliance today by U.S. Navy afloat units on satellites and highly complex electronics, all of which are vulnerable to compromise or destruction by an enemy, can also leave us highly vulnerable, particularly if our ships and Surface Warfare Officers are not trained in more traditional methods of navigation and seamanship.

Losing satellites could badly compromise or eliminate satellite navigation. Funny, I trusted the star fixes, but the GPS readings that came later, were suspect. As this Log Entry points out, satellites are vulnerable. They can be hacked or “taken out” in a variety of ways.

But with training, a sextant, the right tables and a handful of stars or a noon day sun, the cosmos will tell you where you are on planet Earth.

Soot, as a weapon? Recalling the Mediterranean Cold War in the Sixties

The watch team cheered, we even heard cheering from PriFly aft of our level. The Captain was happy, the bridge watch team was ecstatic. The Russians on our tail? Not so much! Main Control had “gotten into the War,” and I wrote in the ROOSEVELT’s deck log: “Blew tubes at 1430.”

The In-Port Watch on a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier in the Sixties

Any questions?”

“Not that I can think of,” I replied, then added the required legal response: “I relieve you Sir.”

The fateful words are spoken. From this point on, anything that happens on this watch will be my responsibility.

“Very well, I stand relieved. Quartermaster, LTJG Connors has the deck,” the now off-watch OOD announced to the Watch Team.

I, in turn, step back out onto the quarterdeck to take a look around to see if there are any boats headed towards the ship.

The air is very cold, but refreshing, in small doses.

The far off boats of Cannes, swing in the breeze.

At this distance, the beautiful city rolls itself like a white wave, far into the hills. On the distant horizon, covers the mountains like a picture post card.

Memories of the Fru Dee Roo

When the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CV A-42) was towed toward the oblivion of the scrap yard in 1978, she consisted of some 65,000 tons of obsolete steel and equipment–but she left many more tons of memories with the tens of thousands of Navy men who had served aboard her during her 32 years of commissioned service.

The “Rosy” or “Fru Dee Roo” or “Rusty Bucket” to those of us who alternately cussed her amongst ourselves and who fought for her honor with outsiders, was more than just a ship. She was home for some 4,000 men–a floating “town” some 1,000 feet long with over 500 miles of wiring, 150 television receivers, 111 storerooms where some 81,000 items were kept in readiness, and with 12 oil-fired steam boilers that drove it at speeds up to 32 knots. A bit of a “gas hog,” the ship’s boilers burned some four million gallons of fuel per month on average. This “town” carried over 70 warplanes of many types and could launch them at a rate of two per minute.

We were “the stick” in case the “talk softly” part was not successful.

What The Hell Flag Signal

The day the ROOSEVELT got the What the Hell Flag Signal. As the OOD, you knew you had really screwed things up when an oiler gave you the “What the Hell” Flag Signal.

On this afternoon, as we were making our high speed approach on the oiler, the Captain suddenly announced that he had the conn (was maneuvering the ship himself), then announced that Commander “Neversail” had the conn. I was amazed. I assumed that he wanted the new Navigator to get some experience, but to actually let him maneuver the ship (with the Captain making “recommendations” while standing right beside him), was risky as we were barreling down on the unsuspecting oiler. “Things” didn’t go well, as they say.