Is it ethical can often be determined by asking: when I am vulnerable, can I trust you?

Perspectives on Ethics

Ethics and Social Theory

Hosmer (1995) traces the fundamentals of ethics to a variety of social theories that deal with an individual’s need to feel secure – to be comfortable in approaching interactions with others, particularly dependent interactions, and trust in a favorable outcome. When people trust, they willingly increase their vulnerability to the actions of others whose behavior is beyond their control. When people trust, they consciously regulate their dependence on someone else in various ways depending on the person, the task, and the situation. In other words, when we trust we except our vulnerability and dependence on the actions of others because a greater good is expected to be attained.

The act of trusting includes the expectation that the person organization on whom we are depending will perform an action or provide a service in a way that is beneficial to us and not detrimental. These expectations explain why we forgo or delay taking defensive actions. Hosmer (1995) explains trust based on four moral values, including:

- integrity (our assessment of the person organization’s honesty and truthfulness);

- competence (the collective evaluation and assessment of interpersonal skills and technical knowledge needed to successfully perform the function we are seeking);

- consistency (predictability and good judgment); and,

- reliability (their willingness to protect and support our interests, to do so willingly, and to freely share ideas and information).

Ethics

The process of elaborating upon and acting according to our value structure, i.e., ethics, represents values in practice, as well as the assessment and critique of values. When values, responsibilities, or rights, are in conflict, an ethical dilemma can present itself (Mitzen, 1998).

Ethics is a process that includes analyzing and assessing those components used to define and justify morality in its various forms, e.g., logic, values, beliefs, and principles (Cooper, 2006). Ethics considers the articulated or mandated moral code and examines it to better determine its meaning and purpose. Ethics attempts to explain and assess moral conduct through systematic reflection and reasoning (Cooper, 2006). Descriptive ethics attempts to identify and explain the underlying assumptions and connections to conduct. Normative ethics articulates supportable cases and arguments for particular conduct in a specific situation (Cooper, 2006).

Ethics has two essential orientations: deontological (duty to uphold ethical principles without regard for the consequences of one’s actions); and, teleological (concern for the consequences or outcome of one’s conduct). As Cooper (2006) points out, ethics should involve a more systematic consideration of the values and principles that effect the choices we make, their consistency with our duties, and the incident consequences toward which they lead.

Ethical Dilemma

A dilemma (from Greek, ambiguous situation), apparently forces us to choose between two, often contradictory, alternatives. I say “apparently,” since a reasoned, deliberate and orderly assessment of the issue can often produce different alternatives, much better suited for solutions or resolution. As an aside, this form of false or fallacious reasoning – is known as false dilemma (or false dichotomy, fallacy of bifurcation, or black-or-white fallacy).

Meneghetti and Seel (2001) emphasize the importance for NPO executives to be able to deal with real-life ethical dilemmas that are both rich and context and consequence. An ethical dilemma, they explain, typically includes five fundamental characteristics:

• it is hard to name precisely;

• it is embedded within a specific individual or organizational context;

• it may not even be obvious;

• the claims of multiple stakeholders are involved and should be addressed; and,

• that involves a situation where the manager or leader wants or intends to do the right thing, but may not know what the proper course of action may be or how to accomplish it (Meneghetti & Seel, 2001).

The authors outline a four-step ethical decision-making model in which: the primary stakeholders are identified; the problem is addressed from the point of view of each of the identified stakeholders (including the key ethical values being violated); actions determined that should be taken given each stakeholders concerns; and, a decision finalized once the positive and negative consequences of each action are better known. The objective, they explain, is to choose the option that, on balance, minimizes harm, reduces negative consequences, and produces the greatest balance of good in the long term (Meneghetti & Seel, 2001).

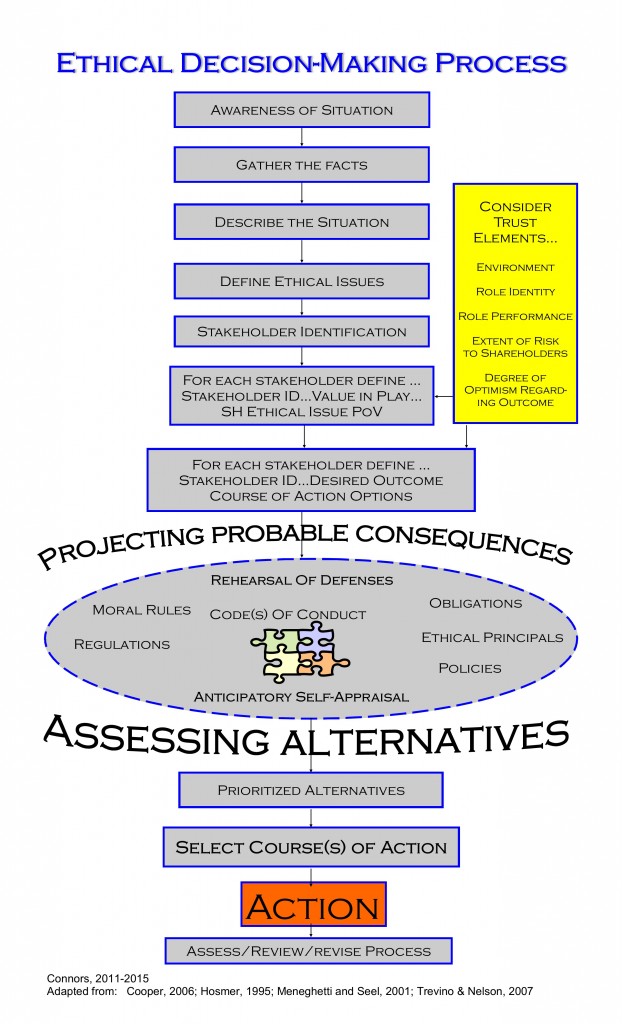

In my view, both models could be strengthened by incorporating their relevant steps into a rational model that suggests a more nuanced process. The following model represents an ethical decision-making process incorporating the views of both Cooper and Meneghetti and Seel (2001).

Ethical behavior

Typically, we can identify three major areas where ethical problems can arise, according to Mitzen (1998), including: business practices; employee relations; and, interactions and relations within the larger community or external operating environment. Ethical behavior toward its own staff and volunteers should be a foundation and a given for any nonprofit organization. This includes meaningful communication, and a supportive environment where even whistle blowing, with its inherent potential for divisiveness and conflict, is seen as an expression of several fundamental core values, e.g., responsibility to the publics being served. Organizational core values should be clearly articulated, and clear policies developed as to how they are operationalized.

Nonprofit organizations should have “organizational ethics mechanisms,” that identify how the organization educates its people regarding ethics related issues and how it integrates ethics into its operations and organizational structure (Mitzen, 1998).

Ethical decision making model

Cooper (2007, p. 31) introduces his readers to a five-step ethical decision-making model, the objective of which is to challenge us to think about what is needed to move from an ethical problem facing us, to a reasoned, orderly, sequential course of assessment and analysis intended to resolve or solve the challenging issue. His model represents a framework through and by which a determination can be reached and a rational, fact-based decision achieved for the most promising course of action. The author correctly points out that no on model can provide the single best possible or “correct” solution. It can however, provide a template through and by which the problem is assessed, evaluated, and converted into an opportunity to creatively designed “the best solutions for a given individual in a specific situation within the uncertainties and time limits of real administrative life” (Cooper, 2007, p. 30).

Rather than accept Cooper’s ethical decision-making model as the definitive illustration for the steps in ethical decision-making process, we should remember there are a wide variety of potential models suggested proposed for decision-making, in general. Depending on the situation, those faced with an ethical issue or dilemma might well consider using Cooper’s model and others as guides that can be adapted to the situation, producing a more specific and situationally focused ethical decision-making model.

As McDermott (2011) points out, there are a number of decision-making models from which to choose. The manager even has to make a decision as to the one best suited for the situation, e.g., rational models, intuitive models, rationalist-iterative models, as well as models that have been suggested in a variety of “steps.” Cooper’s model most closely resembles the six-step, rational decision-making model that includes the following phases: define the situation and the desired outcome; research and identify options; compare and contrast each alternative and its consequences; make a decision or choose an alternative; design and implement an action plan; and evaluate results (McDermott, 2011).

Figure 1 Ethical Decision-making process model

Role

The term “role” has its origins in medieval Latin and the word ro(tu)lus, a roll of parchment, that in turn was derived from earlier Latin rotulus, a small wheel. In the Middle Ages the part or character played by an actor in a dramatic performance was written out on a rolled up parchment or paper. The part soon became associated with the means used to describe and explain what the character did in the performance–a role. Keeping the etymology of the term in mind helps us better understand the meaning and implications of the term as it is used today.

Luthans (1995) explains that a norm – the typically unwritten but generally understood rules of a group, culture, or society for behaviors that are considered not only acceptable, but expected – represents the “oughts” of behavior. Collections of norms represent prescriptions for acceptable behaviors expected by, and sometimes determined by, the group.

A role consists of a defined set and pattern of norms associated with a position (defined or undefined but “understood” by the group), that is filled or acted out by an individual. A role can perhaps best “be defined as a position that has expectations evolving from established norms” (Luthans, 1995, p. 380).

Roles in Management

A role is an organized set of behaviors identified with a position, Mintzberg (1975) explained. He noted that formal authority is the basis for three interpersonal roles, leading to three informational roles. Together, the interpersonal and informational roles provide the tools to play four decisional roles.

Interpersonal relationship roles, include: figurehead role (ceremonial duties); leader role (responsibility for the work of the people in the unit–hiring/firing, motivation, encouragement); and, the liaison role (contacts outside the immediate work unit).

Informational roles, include: monitor and disseminator (collecting/disseminating soft information for his unit/organization); and spokesman (collecting, positioning, and sharing information with outsiders.

Decisional roles include: entrepreneur (identify new ideas and pursuing opportunities that advance the organizational unit’s objectives); disturbance handler (responding to changes and pressures affecting performance of the unit organization); resource allocator (decisions relating to allocations of resources and the empowerment of subordinates decisions and program contributions).

Collectively, Mintzberg (1978) suggests the managerial role represents a gestalt – an integrated whole greater than the sum of its individual parts. The managers performance depends directly on the extent to which he or she understands and effectively response to the demands and dilemmas of the position. Although often tempted by the short-term benefits of “busy work”, managers should resist the pressures of superficiality by giving serious attention to those issues that require it by keeping the broad picture in mind and by using a variety of analytical inputs” (Mintzberg, 1978, p. 60).

Values

The term we use to describe the worth of an object or concept – its monetary status, desirability, usefulness, importance to the possessor, utility, or merit – is “value.” The term can be traced back to its Latin roots of “valere,” to be strong, to be of value. It can even be traced back to the Indo-European language, from which so many of our present day languages originate, where it meant “to be strong,” “to rule,” “force,” or “power” (Morris, 1981, p. 1415).

Values typically refers to those “strong and enduring beliefs that motivate and define behavior. Values inform the choices we make. They are a statement of what is ‘good’ for individuals and for society” (Mitzen, 1998, p. 103). Values define those things we believe in, and what we consider important in our life and work.

Meneghetti and Seel ( 2001) point out, values represent strongly held attitudes and beliefs regarding what is desirable. However, not all values necessarily have an ethical component, e.g., power per se is neither good nor bad. Those values not having broad societal implications and that are typically held private are considered morals. These attitudes and beliefs held by individuals regarding what is worthwhile or good, are derived from and influenced by family, culture, society, and religion. Typically, public values are considered ethical values, more universally accepted beliefs about what is right or wrong.

Values and Roles

Each role “comes equipped” witha set of values attached that reflect guidelines to behaviors expected for those “playing” that part, e.g. leader value of “cheerleader” (motivator).

Discriminatory behavior

Discrimination includes treating or considering, or making distinctions regarding a person or some other entity based on the group, class, or category to which that person or entity belongs, rather than on individual merits (USLegal, 2011). Trevino and Nelson (2007) explain that discrimination can occur in cases where considerations other than qualifications affect how an employee or associate is treated. For example, the committee identified a minority member to survey a minority population on an issue that should have had nothing to do with one’s identification with or membership of a group other than that of “employee.”

Discrimination represents an important ethical issue and problem in the workplace due to its corrosive effect on perceptions of fairness. When the workplace is not fair, ultimately our entire legal system promising justice and protection of individual rights is in jeopardy.

Many case studies reviewed by students outline possible cases of de facto discrimination that could rapidly devolve into the condition known as a “hostile work environment.” Further, the conditions as outlined in some case studies, if valid (not simply perceived) could meet the requirements for an official investigation, followed by official action.

Values conflicts and ethical dilemmas

Values conflicts presented as ethical dilemmas will certainly face all of us as managers from time to time, and there may be no completely satisfactory resolution. This eventuality must not be used to rationalize their moral or unethical behavior.

Codes of ethics, although helpful, cannot be depended on to solve all values conflicts. In fact, some may use them to appear to “stay within the law” while actually infringing on truly ethical conduct.

Unethical actions can really be hidden and self enforcement helps insulate the manager and the organization from external scrutiny, or enforcement. Finally, as leaders and managers of our respective organizations, we have a personal and professional interest in being alert to potential ethical dilemmas in situations, and to employ an orderly ethical decision-making process to seek effective resolution.

Morals

Morals or morality, originating from the Latin word for “custom,” typically refer to those judgments and characteristics of our actions that can be defined according to our core values as good” or “bad/evil.” Morality is assessed using various standards or precepts of goodness or codes of behavior. Morality represents a set of customs within a society, class, or social group that attempt to regulate relationships and prescribed behaviors that enhance the group’s survival (Morris, 1981, p. 853).

Morality is based on presumption of what is an accepted mode of behavior that is established or provided by an authoritative source, e.g., religion, culture (including that within a group organization), social class, community, or family (Cooper, 2006).

Ethos as Moral Custom

The Greek term for a moral custom was ethos, a meaning which has expanded for hundreds of years to now include a principle of right, correct, or good conduct, including a body of such principles. Ethical came to mean a practice that was conducted within the accepted definitions of right and wrong, and governed the conduct of the group. Ethics represents the general study of morals, including the rules or standards by which the conduct of a group or profession are evaluated and judged (Morris, 1981).

Codes of Conduct

Organizational codes of conduct – ethical standards – can be seen as articulations and declarations of core values and acceptable behavior on the part of the individual or organization that its actions and decisions can, indeed, be trusted. Applied to ethics, Hosmer (1995) suggests that trust is the result of behavior that recognizes and protects the interests of others – the overriding goal being to increase cooperation and achieved benefits within a joint endeavor or exchange.

Trust is a relationship in which some personal or organizational vulnerability is accepted because our analysis suggests a collective, general optimism is justified in a mutually beneficial outcome based on expectations or conditions of moral (socially expected and /or defined as acceptable) behavior.

Codes of ethics and conduct such as those endorsed by APA, represent the standards of practice supported, espoused, and directed by that organization. The codes delineate and outline the collective values of that professional organization, and typically cover a number of ethical areas and considerations. Most codes of ethics and conduct include two major components, including: definitions and explanations for recommended or mandatory professional behavior on the part of those professionals practicing in that field; and, what Kocet (2006) explains is encouragement regarding ethical reflection to help clarify and improve the fundamental ethical beliefs held by that profession.

A hypothetical but realistic scenario facing some NPO leaders and managers today might be assessed using this blended model along the following lines…

Awareness of situation…

The human services nonprofit organization for which you serve as the Executive Director, has recently lost the source of revenue on which the organization depended to fund the volunteer resource manager position.

Situational description…

In an effort to balance the organization’s budget before reaching a dangerous state of insolvency, the organization’s personnel committee, comprised of three members of the Board of Directors, has met and is prepared to recommend the termination of the paid staff position of volunteer resource manager, in favor of replacing that staff member with a volunteer.

Stakeholder identification…

Board of Directors

Their loyalty to the organization and their sense of fiduciary responsibility, represent important core values in play.

NPO senior staff

Loyalty to the organization, loyalty to staff, fairness, professionalism, teamwork, integrity, and mutual respect are among the core values initially identified as important to senior staff members.

Volunteer resource manager

Security, fairness, loyalty, professionalism, are all expected core value issues with the staff member most directly affected by the committee’s recommendation.

There are other potential stakeholders that could be considered in this explanation, e.g., the organizations volunteer corps, the membership, clients depending on the volunteer services, and the community at large.

The Board of Directors feels a primary responsibility to their fiduciary duties and seeks an outcome of a balanced budget.

The senior organizational staff are quite concerned about the negative ramifications of a pending termination on the organization’s morale and esprit de corps, its operational effectiveness in light of a change in volunteer management from seasoned professional to an individual lacking equivalent training, and the devastating economic consequences to the soon-to-be former volunteer resource management professional. The senior staff would prefer to retain their colleague and to ensure the continuation of the organizations exemplary record in human services delivery through its effectively managed volunteer resource program.

The volunteer resource manager, although not yet aware of the pending recommendation from the committee, can certainly be expected to be devastated by the news. The potential for “political” fallout from the individual should be considered significant. Clearly, their desired outcome would be that the issue never presented itself in the first place, and that they be retained in their present position.

Selected course of action: following a confidential meeting of the senior staff in which the situation was reviewed in great detail in terms of ethical principles, moral rules, and potential ramifications, the senior staff voted to accept a temporary 5% pay cut to ensure the continuation of the volunteer resource manager until additional funding sources could be identified. The group decision unified the staff around a common purpose, reaffirmed important core values for them and for the organization, and upheld the Board of Director’s fiduciary responsibilities, including the continuation of a balanced budget.

Ethical perspective in NPO management literature since 1980

One approach to achieving better understanding of an emerging trend is to do so within what could be seen as an historical perspective or framework. In this case, the baseline for the framework is the publication in 1980 of the first Nonprofit Organization Handbook (Connors, 1980).

The handbook was organized around the premise that regardless of the specific human service provided by a nonprofit organization, all shared seven fundamental areas of management, including: organization and corporate principles; leadership, management and control; sources of revenue; human resource development and management; fiscal management (budgeting, accounting, and record-keeping); and, public relations and communications.

A review of the index for this first edition reveals a single entry under the category “ethics.” The context in which it was used within the book was an observation that “a growing number of nonprofit organizations now employ a professional manager, a full-time paid employees and supervisors and is responsible for the daily routine business of the organization” (Connors, 1980b, p. 2-70). The single reference to ethics and this major handbook appeared when the author noted that the area of managing nonprofit organizations has become a profession itself “with its own high code of ethics and standards” (Connors, 1980b, p. 2-70).

Over the next 21 years five subsequent major handbooks focused on nonprofit organization management were published, the latest in 2001 (Connors, 2001). A review of the index for this volume offers a startling contrast to the first NPO handbook. The subject of ethics appears throughout the book with multiple page coverage focused on ethics in all aspects of managerial behavior and policy, including: behavior; budgeting; compensation practices; fundraising; human resource management; international business; and, numerous mentions of professional codes of conduct. An entire chapter is devoted to “Ethics and Values in the Nonprofit Organization” (Meneghetti & Seel, 2001). Clearly ethics is now understood to be a critical component of NPO management and decision-making.

Ethics and Public Trust

Dr. Joan Pynes contributed a most important chapter to the The Volunteer Management Handbook (Second Edition), entitled, “Professional Ethics for Volunteers” (Pynes, 2011). The author points out that to survive nonprofits must maintain public trust. One important component of that collective trust is based on paid staff and organizational volunteers fulfilling their responsibilities in a lawful, ethical, and competence manner. This objective far exceeds simply complying with formal controls, program reports, and financial audits. Instead, it is vitally important that nonprofits establish an aspirational internal ethical climate.

Pynes (2011) recommends that NPO managers establish a strategic human resource management program that uses defined and formal systems within the organization to ensure the most effective use of staff and volunteer resources to fulfill the organization’s mission. There is no doubt the nonprofit sector currently faces many daunting challenges. Nor is there any doubt that new problems and changes within external and internal environments will constantly present themselves to all of our managers and leaders.

The people on whom our nonprofits depend to fulfill our organizational missions, are highly affected by the cultures we establish within which they must participate and contribute. Clearly articulated values, ethical principles, and codes that explain how our ethics are interpreted and used for action and decision-making, are highly significant –they define our culture and the relationships between those who were members of that culture. When inevitable ethical dilemmas present themselves, the successful NPO executive will know to follow a well-defined ethical decision-making process to find the best possible solution or resolution.

Suggested citation:

Connors, T. D. (2016, February 17). Perspectives on ethics: When I am vulnerable, can I trust you? [Is it ethical can often be determined by asking: when I am vulnerable, can I trust you?]. Retrieved from NPO Crossroads: http://www.npocrossroads.com/management/perspectives-on-ethics-when-i-am-vulnerable-can-i-trust-you/

References

Connors, T. D. (1980). The nonprofit organization handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cooper, T. L. (2006). The responsible administrator: An approach to ethics for the administrative role (5th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass/Wiley.

Hosmer, L. T. (1995, April). Trust: The connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 379-404. doi:10.5465/AMR.1995.9507312923

Kocet, M. M. (2006, Spring). Ethical challenges in a complex world: Highlights of the 2005 ACA Code of Ethics. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(2), 228-234.

Luthans, F. (1995). Organizational behavior (7th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

McDermott, D. (2011). Six step decision making process [Web page]. Retrieved April 16, 2011, from Decision-making-confidence.com: http://www.decision-making-confidence.com/six-step-decision-making-process.html

Meneghetti, M. M., & Seel, K. (2001). Ethics and values in the nonprofit organization. In T. D. Connors (Ed.), The nonprofit handbook: Management (3rd ed.) (pp. 579-609). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Son.

Mintzberg, H. (1975, July). The manager’s job: Folklore and fact. Harvard Business Review, 53(4), 49-61.

Mitzen, P. (1998, Fall). Organizational ethics in a nonprofit agency: Changing practice, enduring values. Generations, 22(3), 102.

Morris, W. (. (1981). The American heritage dictionary of the English language. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton-Mifflin Company.

Special population law & legal definition [Special population is a term that is generally used to refer to a disadvantaged group.]. (2010). Retrieved June 10, 2010, from Special population is a term thatis generally used to refer to a disadvantaged group.: http://definitions.uslegal.com/s/special-population/

Trevino, L. K., & Nelson, K. A. (2007). Managing business ethics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Son.