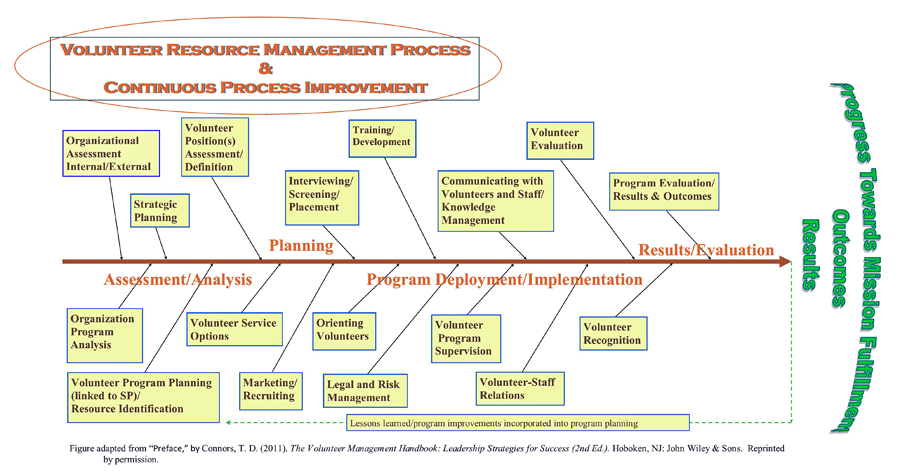

Management activities taking place within a typical volunteer resource management program when arranged in the logical sequence derived from the PDCA continuous improvement cycle concept provide program leaders with the ability to establish and sustain a volunteer program that learns from its successes and constantly improves as performance.

The link between our national quality of life and volunteer motivation

All of us want the best quality of life possible for ourselves, our families, and her fellow citizens. A strong case can be made for the vital role our charitable-philanthropic organizations play in determining our nation’s overall quality of life.

Charitable, nonprofit organizations, by definition, exist for a variety of public purposes, the majority of which, in the form of providing a wide variety of human services, make significant contributions to the nation’s overall quality of life.

Just over1,000,000 charitable, philanthropic organizations provide an astonishing number and variety of human services that, collectively, help shape America’s overall quality of life.

Sustaining and enriching the overall quality of life in our communities through improvements in human services is a worthy, broadly supported social and moral goal.

Since the great majority of these hundreds of thousands of charitable organizations depend upon the services of volunteers in order to fulfill their missions and purposes, we can see how important volunteer resource management is when it comes to sustaining or improving our nation’s quality of life. There is a direct link between the overall effectiveness of volunteer resource management by our charitable and philanthropic organizations and our nation’s quality of life.

We tend to refer to the collective group of dedicated, grassroots philanthropists who offer their services of their own free will to charitable-philanthropic organizations as a demographic segment called “volunteers.” In the broadest sense of the word that is true, but only as a construct that has the meaning we give it. These volunteers can be of almost any age, come from any segment of our society, have a wide range of educational backgrounds, have – or not – have a myriad of skills and abilities, and perform a vast range of services for these organizations, whose collective human services comprise so much of what we term quality of life.

Why Volunteers Volunteer…

The term volunteer means “of their own free will.” It typically means without expectation of monetary rewards or remuneration. People serve charitable-philanthropic organizations of their own free will and without expecting compensation for a number of reasons. Depending on the reason an individual decides to volunteer, the most effective motivation or combination of motivations might be quite different. Volunteer opportunities are not always labeled as such. They could be internships, community service positions, or self-learning opportunities. Volunteer resource managers will need to keep these various categories of volunteer in mind as they best determine the most effective combination of motivational strategies to use.

A quick Google search for the term “motivating volunteers,” returned 8,120,000 results results in .31 seconds. Clearly, a great deal has been published on this important topic.

When we talk about “volunteer motivation,” we mean those influences that are at work in determining how a person behaves toward our organization. Motivation can be either positive or negative, and, measuring motivation is very difficult. However its strength can be inferred based on how a person’s behavior toward our organization changes or how its intensity varies. People serve philanthropic organizations for many different reasons and in many different ways. No “one size fits all” is certainly true for our charitable organizations, how they are managed, and the reasons why people volunteer for particular organization.

Good, generic advice is at your fingertips…

Our Google search provided some good information on motivating volunteers that we should keep in mind. We should ensure our research begins with articles and information that address the fundamental motivators responsible for why people work for an organization “of their own free will.” To be effective as a volunteer resource manager, you need to have a fundamental understanding that motivation to volunteer is not a quality that you and, but rather a response and behavior that you identify and nurture. Motivations come from within.

The better we understand why people behave as they do, and apply that knowledge to fulfilling our organization’s purpose and mission, is the extent to which our efforts to recruit and retain volunteers will be successful.

For example, some typical recommendations from the “secrets of volunteer motivation” type articles, include:

• providing positive feedback

• rewards and recognition

• providing on-the-job vocational training

• providing perks such as refreshments and comaraderie at your facility when they volunteer

• hiring staff that are trained and committed to volunteers

All of these recommendations are fine…as far as they go.

Using the volunteer resource management model…

The first nonprofit organization handbook was published in 1980. Subsequently, that area of management practice grew rapidly and is now understood to be a separate field of management science. The first volunteer resource management handbook was published in 1996. The most recent was published in 2011 (Connors).

The field of management practice for volunteer resource programs has developed substantially since publication of the first volunteer management handbook. One of the most useful management tools for VMR’s is the representation of a typical volunteer resource management program.

As volunteer resource management science has evolved, we have learned more about the various management actions and activities that are used within a typical program. Further, if we arrange these activities in a logical sequence – from planning through evaluation – we can suggest a program design management model – sequencing the activities to give us more ability to establish and sustain a volunteer program that learns from its successes and constantly improves its performance.

In other words, the model reminds us that a successful volunteer resource management program has important components, many of which do not receive the attention they deserve in terms of their importance to overall program results. Further, the model gives us the ability to look at important program objectives, e.g. motivating volunteers, from a new perspective.

Volunteer Resource Management Model

When we look at the range of volunteer resource program management actions and activities, we can see that they can be aggregated and modeled as a process that includes four basic steps or phases: assessment/analysis; planning; program deployment/implementation; and, results/evaluation. Each of these phases contains opportunities for successful volunteer resource managers to reinforce those reasons the volunteer considered when they were making their decision to affiliate, train, serve, and extend their commitment to your organization. Each organization that uses volunteers is able to deduce because it offers these volunteers enough reasons for them to participate in serve of their own free will. Often, we think we understand what these reasons are. But, do we?

Each volunteer is an individual devoting his or her service and loyalties to a specific organization at a specific time. Therefore, not all typical “best practices” apply to all volunteers, organizations, or situations. Rather than simply adopt such best practices, we must instead thoughtfully adapt them to our programs and our organizations. The volunteer resource management model can serve as an important tool in that process. Using the model, we can focus on what the model suggests to better understand what we should know and/or keep in mind as we adapt well intended best practices to our organization.

Volunteer motivation is both a process and a culture

Volunteer resource managers are always alert to management practices that help them improve their abilities to motivate potential and actual volunteers.

There are opportunities – and pitfalls – to motivate – or de-motivate – volunteers at every stage along the continuum of the volunteer resource management model. Attention should be given to practices and policies that affect volunteer recruitment, performance, and retention throughout the volunteer’s lifecycle.

For example, even before recruiting begins the organization should know exactly what potential future volunteers will do to help the organization fulfill its mission and purpose. That means position descriptions that not only clearly describe the duties, responsibilities, authorities, and obligations of a particular position, but relate the results of that position to the organizations mission and strategic planning.

Once the potential volunteer has been motivated enough to affiliate with the organization, that commitment must be sustained through orientation and whatever training may be required for the incumbent of the volunteer position. These requirements very, of course, depending on the position, its responsibilities, and the nature of the organization or human service being provided. As with a professional staff member, any direct contact with clients receiving a human service must be carefully thought through beforehand, and appropriate orientation, training, and supervision plan policy must be established.

Once the volunteers properly recruited, oriented, trained, and in place assisting the organization as outlined in their position description, motivation then turns to practices that will help sustain their commitments not only to the organization but to excellence in the services they provide on behalf of the organization.

Motivation operates at every stage of the volunteer life cycle

VRM’s need to first understand their organization, its mission and purpose, and the organizational culture that currently exists for its volunteers. Then, using that as a baseline, they should analyze their organization to better understand the various types of volunteer opportunities that exist and what the respective motivations might be for these opportunities.

Volunteer resource program managers should know and/or determine the specific reasons why their organization attracts and retains volunteers – or not. The following discussion is organized around the four stages suggested by the volunteer resource management model. Overall, it underscores the importance of program planning by the volunteer manager, and the careful alignment of the volunteer program with the organization’s overall strategic plan and its deployment.

Phase 1: Assessment/analysis

- What combination of management, leadership, and program activities are required for our organization to fulfill its purpose and mission?

- What do we have to do in order to be successful?

- How do our activities logically aggregate themselves into areas of responsibility, e.g., positions filled by people – paid staff and/or volunteers?

- How do these respective positions contribute to our ability to fulfill our mission?

- To what extent have we thoughtfully analyzed and articulated these areas of responsibility and activity into position descriptions that explain and outline in detail the nature of these positions, including: duties, responsibilities, authorities, training, evaluation, and risk factors?

In the assessment and analysis phase of volunteer resource planning, we should know with some exactitude what positions:

• are truly required by our organizations if they are to fulfill their purpose and mission;

• will be paid staff; and,

• which will be volunteers without financial remuneration.

• We should also know how long it is been since a “zero-based” assessment was done of the organization’s human resource needs.

Phase 2: Planning

The planning phase includes the creation of position descriptions that insofar as possible fully explain the duties, functions, contributions, and risks that are foreseen for each position.

An assessment of the full range of position descriptions enables the volunteer resource director to better understand what recruiting themes and media will be most successful. Different positions may require specific messages in recruiting communications, and various media mixes, as well.

This personnel analysis can also suggest the management and leadership structure that will need to be in place in order to:

• effectively coordinate staff and volunteer services;

• put into place the policies that will be needed in order to ensure both effective and efficient management of human resources within the organization; and,

• establish policies and processes for evaluation of all programs within the organization an annual basis, including personal evaluations needed for salary adjustments (in the case of paid staff), and/or recognition and awards.

Phase 3: Program deployment and implementation

The program deployment and implementation phase of a volunteer management program includes such important components as: overall program supervision, training, legal and risk management, volunteer-staff relations, communications, volunteer evaluation, and rewards and recognition. Each of these management functions should be individually reviewed and assessed for their potential to deepen bonds between the volunteer and the organization, or to become a de-motivator.

Careful thought should be given to the overall structure of the volunteer resource program. Typically, the more programs and volunteers included within the program, the more structure is required for effective management. In turn, the structure will influence the number and type of staff positions (not necessarily paid staff) that will be required for effective program implementation. Of course, each of these positions will need to be defined as to roles and responsibilities, and identified as to its place within the overall management structure.

The volunteer program handbook should be user-friendly and should contain information about the organization, including its mission, purpose, history and workplace policies and procedures. The volunteer orientation placement phase should ensure that all volunteers have a good working knowledge of this important document.

Phase 4: Results and Evaluation

While personnel evaluations for volunteers typically do not receive the attention and priority they deserve, they are very important to both the volunteer and the organization. The organization needs to have a defined and workable system by and through which it evaluates all of its human resources, including volunteers. This evaluation helps ensure that performance is mission-enhancing, and that it was conducted with the highest standards. Evaluations can help identify areas of improvement by both the organization and the volunteer. Evaluations are also needed to provide a supportable basis for personnel actions ranging from retention to dismissal – and as a basis for awards and recognition.

Bibliography

Barisco, M. (2013, June). [Review of the book the volunteer management handbook: Leadership strategies for success (second edition), by t. d. Connors (ed.)]. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(3), 624-626. doi:10.1177/0899764012457865

Browning, J. W. (2013). Leading at the strategic level. Washington, DC: National Defense University.

Connors, T. D. (1980). The nonprofit organization handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Connors, T. D. (1992, August 1). Avoiding ‘quality shock.’ Nonprofit World, 10(4), 25-29. Retrieved from http://proquest.umi.com.library.capella.edu/pqdweb?did=671169&sid=2&Fmt=3&clientId=62763&RQT=309&VName=PQD

Connors, T. D. (1993). The nonprofit management handbook. New York, NY: John Wiley.

Connors, T. D. (1995). The volunteer management handbook. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-0471371424.html

Connors, T. D. (1997). The nonprofit handbook: Management (2nd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Connors, T. D. (2001). The nonprofit handbook: Management (3rd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley.

Connors, T. D. (2001). The self-renewing organization. In T. D. Connors (Ed.), The nonprofit handbook: Management (3rd edition) (pp. 3-45). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Connors, T. D. (2010, April). Strategic professional development ahead for volunteer managers. The International Journal of Volunteer Administration, 25(1). Retrieved from http://www.ijova.org/

Suggested citation:

Connors, T. D. (2019). Motivating volunteers: What the management model reminds us. In Transformational organizations. Retrieved from BelleAire Press, LLC: http://www.npocrossroads.com/transformational-organization/volunteer-resource-management/motivating-volunteers/